AI agents have gone from toy demos to serious production infrastructure, and 2025 is the year most engineering teams either build with them—or get automated by the ones who do. This blog dives into what agentic AI actually is, why it matters for developers, and how to start building real, production-grade agents with today’s frameworks.

What is Agentic AI, really?

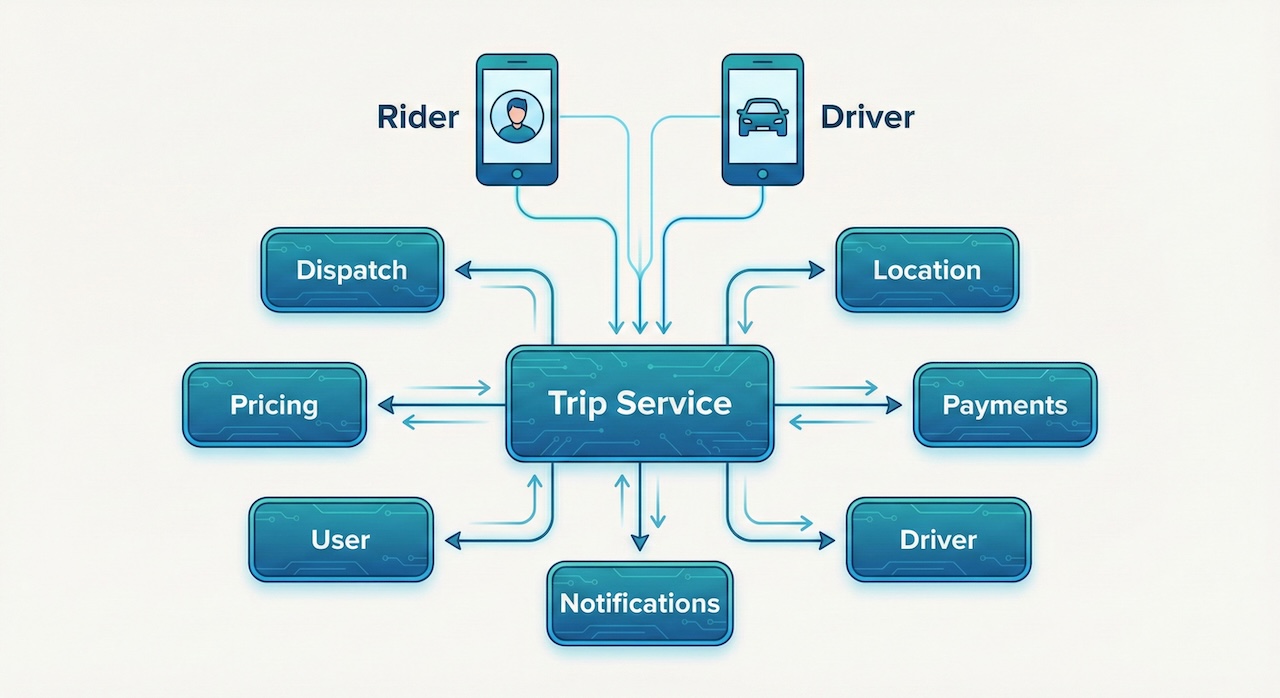

Agentic AI is about systems that don’t just answer prompts—they pursue goals autonomously over multiple steps, calling tools, APIs, and even other agents along the way. An AI agent perceives context, reasons about plans, acts on external systems, and adapts based on feedback, often with a human-in-the-loop for critical decisions.

Compared to classic “chatbot” use cases, agentic systems:

- Maintain state and long-term memory across tasks.

- Plan multi-step workflows instead of producing a single reply.

- Integrate deeply with tools: databases, SaaS APIs, internal microservices, and UIs via computer-use.

Why developers should care in 2025

By late 2025, agents are no longer just research toys; they’re embedded into cloud platforms and enterprise stacks. OpenAI, AWS, and Google now ship first-class “agent” capabilities, with infrastructure for tool orchestration, evaluation, and safety, so engineering teams can ship agents without reinventing the plumbing.

For developers, this shift means:

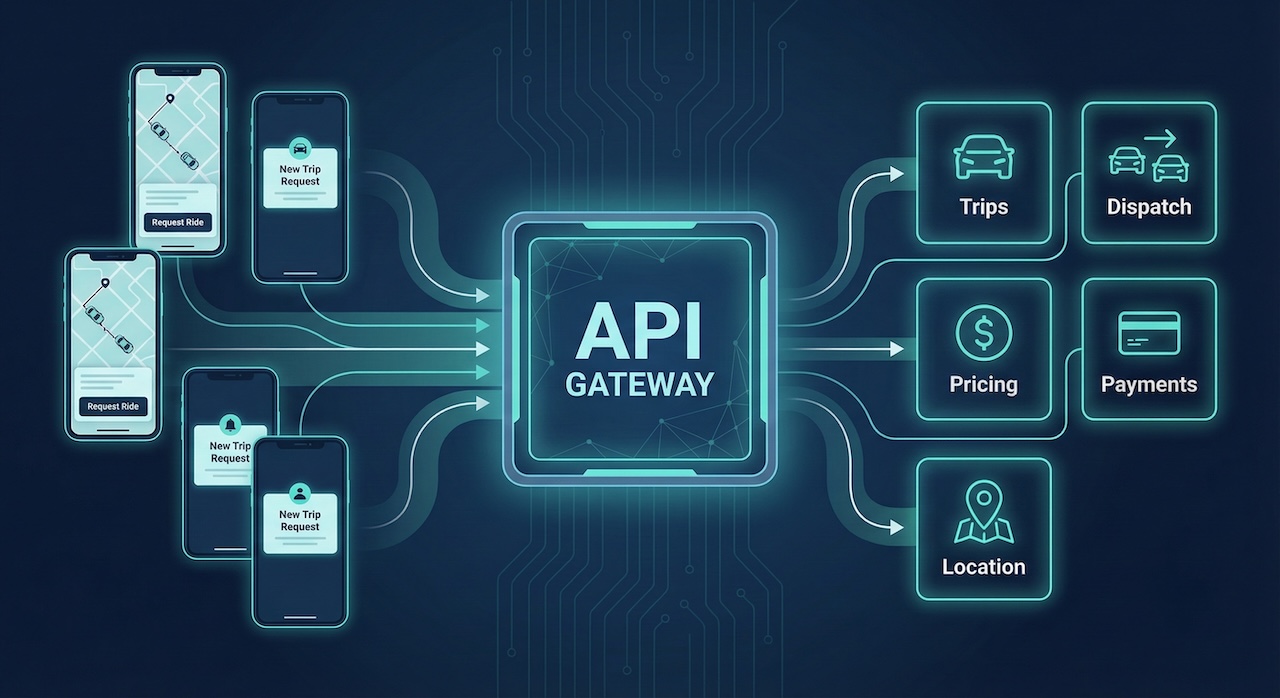

- A new abstraction layer: “agent workflows” join services, queues, and jobs as primitives in your architecture.

- New responsibilities: tracing, debugging, and governing stochastic, partially autonomous systems in production.

- New leverage: one well-designed agent can replace glue code, scripts, and human ops across support, analytics, QA, and marketing workflows.

Core patterns: how modern AI agents are built

Modern agent stacks tend to converge on a few architectural patterns, independent of framework.

1. Tools as first-class citizens

Agents interact with the world via “tools”: structured, typed interfaces around your APIs, DBs, and external services. Each tool exposes a narrow, well-defined capability (e.g., “fetch_customer”, “create_jira_ticket”, “run_sql_query”), and the agent is allowed to choose which tools to call and in what order.

Common tool categories:

- Data access: vector DBs, SQL/NoSQL, search indexes.

- SaaS APIs: CRM, ticketing, messaging, payments.

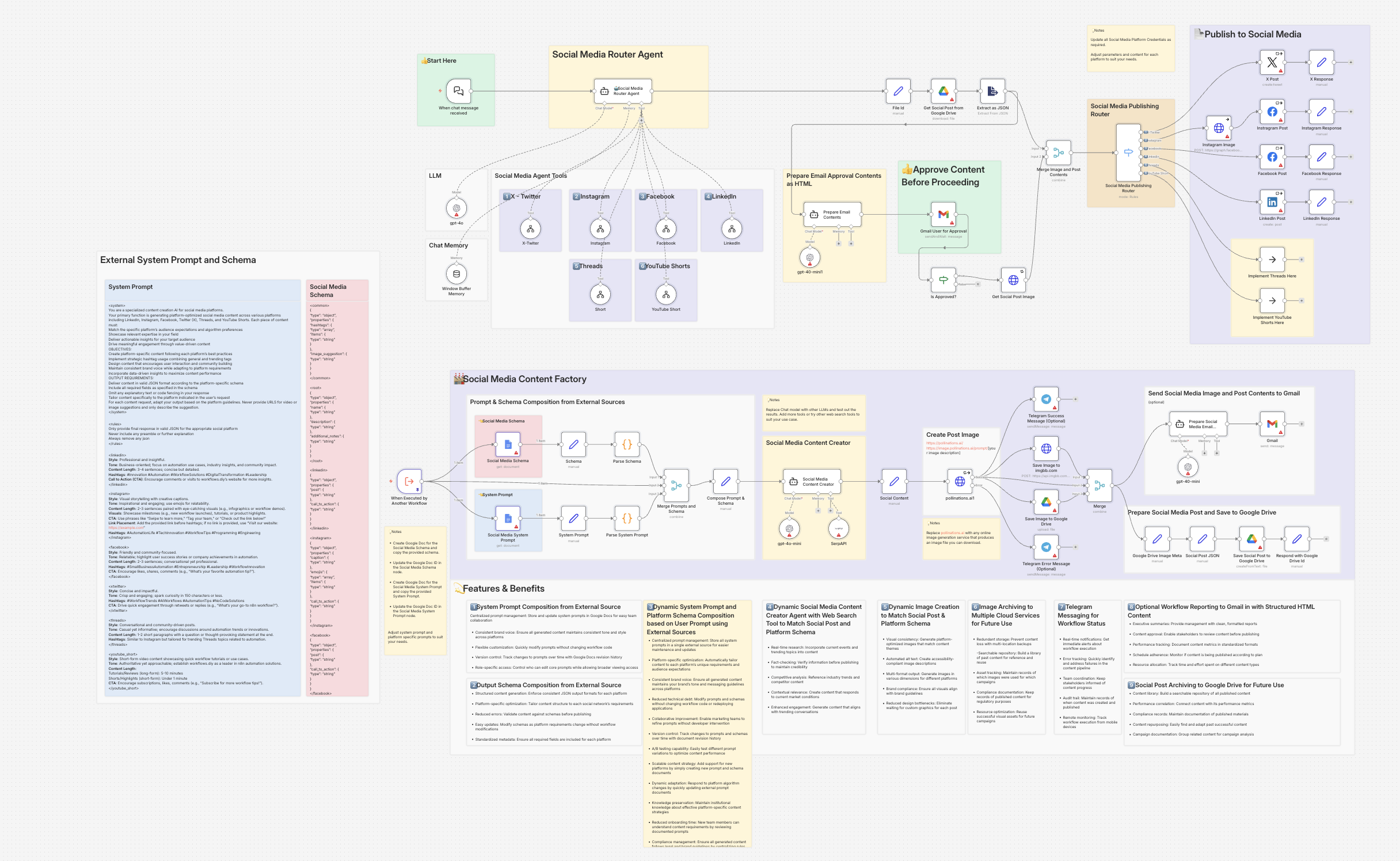

- Orchestration: calling other agents, microservices, or workflows (Zapier, n8n, internal event buses).

2. Planning and reflection

Agentic systems typically combine:

- A planner that decomposes a goal into steps.

- An executor that performs tool calls.

- A reflector that critiques results and revises the plan when necessary.

Frameworks like AutoGen and LangGraph make multi-agent patterns—planner, worker, critic, supervisor—relatively ergonomic for developers, exposing them as Python/TypeScript constructs.

3. Memory and state

Serious agents keep track of:

- Short-term state: the current task, intermediate tool outputs, and partial plans.

- Long-term memory: user preferences, previous tasks, and domain knowledge in vector stores or knowledge bases.

This state is often captured in graphs or DAGs, where nodes are steps or messages and edges represent transitions, retries, or branching logic.

Top agent frameworks developers actually use

Here’s a quick, opinionated snapshot of agent frameworks that matter right now.

Leading frameworks at a glance

These frameworks converge on capabilities like tool integration, memory, workflow orchestration, and observability, but differ in ergonomics and deployment story.

Hands-on: building a goal-driven coding agent

Let’s build a simple, but realistic, coding agent:

“Given a GitHub repository and a plain-English feature request, update the code, open a PR, and post a summary comment.”

This isn’t production-ready, but it demonstrates how to wire tools, planning, and safety using Python and an agentic framework style similar to LangChain + LangGraph.

Step 1: Define tools

We’ll sketch tools for GitHub, repo analysis, and tests. In a real stack, these would wrap official APIs and your CI pipeline.

from typing import List, Dict

import httpx

GITHUB_TOKEN = "ghp_..." # use env vars in real code

def fetch_repo_files(owner: str, repo: str, path: str = "") -> List[Dict]:

url = f"https://api.github.com/repos/{owner}/{repo}/contents/{path}"

headers = {"Authorization": f"token {GITHUB_TOKEN}"}

resp = httpx.get(url, headers=headers)

resp.raise_for_status()

return resp.json()

def create_branch(owner: str, repo: str, base_branch: str, new_branch: str) -> str:

# 1. Get base SHA

resp = httpx.get(

f"https://api.github.com/repos/{owner}/{repo}/git/ref/heads/{base_branch}",

headers={"Authorization": f"token {GITHUB_TOKEN}"}

)

resp.raise_for_status()

base_sha = resp.json()["object"]["sha"]

# 2. Create new ref

resp = httpx.post(

f"https://api.github.com/repos/{owner}/{repo}/git/refs",

headers={"Authorization": f"token {GITHUB_TOKEN}"},

json={"ref": f"refs/heads/{new_branch}", "sha": base_sha}

)

resp.raise_for_status()

return new_branch

def update_file(owner: str, repo: str, path: str, content_b64: str,

message: str, branch: str) -> None:

url = f"https://api.github.com/repos/{owner}/{repo}/contents/{path}"

headers = {"Authorization": f"token {GITHUB_TOKEN}"}

# read current file to get sha

current = httpx.get(url, headers=headers, params={"ref": branch}).json()

sha = current["sha"]

payload = {

"message": message,

"content": content_b64,

"sha": sha,

"branch": branch,

}

resp = httpx.put(url, headers=headers, json=payload)

resp.raise_for_status()

def create_pull_request(owner: str, repo: str, head: str, base: str,

title: str, body: str) -> str:

url = f"https://api.github.com/repos/{owner}/{repo}/pulls"

headers = {"Authorization": f"token {GITHUB_TOKEN}"}

resp = httpx.post(

url,

headers=headers,

json={"title": title, "body": body, "head": head, "base": base},

)

resp.raise_for_status()

return resp.json()["html_url"]

This is standard API integration code: the “agentic” part comes when an LLM decides when and how to call these tools to complete a higher-level goal.

Step 2: Design the agent loop

Next, define a simple planning loop: the model receives a goal and current context, emits a plan plus the next tool to call, and the loop iterates until the goal is reached or a safety limit is hit.

from pydantic import BaseModel

from typing import Literal, Optional

class ToolCall(BaseModel):

name: Literal["fetch_repo_files", "create_branch", "update_file", "create_pull_request", "finish"]

arguments: dict

reasoning: str

class AgentState(BaseModel):

goal: str

history: list # tool calls and results

branch_name: Optional[str] = None

done: bool = False

result: Optional[str] = None

In a LangGraph-style system, this state would be stored in a graph node and passed back through the model at each step.

Step 3: Prompting the “planner” model

A lightweight prompt for the planner might look like this pseudo-code (simplified for clarity):

SYSTEM_PROMPT = """

You are a senior software engineer agent.

Your goal is to implement the requested feature safely.

You have access to these tools:

- fetch_repo_files(owner, repo, path?)

- create_branch(owner, repo, base_branch, new_branch)

- update_file(owner, repo, path, content_b64, message, branch)

- create_pull_request(owner, repo, head, base, title, body)

Rules:

- Always create a new branch before modifying files.

- Never force-push or delete branches.

- Prefer minimal, targeted changes.

- Stop by calling the 'finish' tool with a natural language summary.

"""

def plan_next_action(llm, state: AgentState) -> ToolCall:

messages = [

{"role": "system", "content": SYSTEM_PROMPT},

{

"role": "user",

"content": f"Goal: {state.goal}\nHistory: {state.history}",

},

]

# LLM should output a JSON object conforming to ToolCall

raw = llm.chat(messages) # pseudo-call

return ToolCall.model_validate_json(raw)

Most modern agent frameworks hide this boilerplate under abstractions like “AgentExecutor”, “Node”, or “Graph”, but the concept is the same.

Step 4: Running the loop

import base64

def run_agent(llm, goal: str, owner: str, repo: str, base_branch: str = "main") -> str:

state = AgentState(goal=goal, history=[])

max_steps = 20

while not state.done and len(state.history) < max_steps:

tool_call = plan_next_action(llm, state)

if tool_call.name == "finish":

state.done = True

state.result = tool_call.arguments.get("summary", "Completed.")

break

if tool_call.name == "create_branch":

branch = create_branch(

owner=owner,

repo=repo,

base_branch=base_branch,

new_branch=tool_call.arguments["new_branch"],

)

state.branch_name = branch

outcome = {"branch": branch}

elif tool_call.name == "fetch_repo_files":

outcome = fetch_repo_files(

owner=owner,

repo=repo,

path=tool_call.arguments.get("path", ""),

)

elif tool_call.name == "update_file":

content_b64 = base64.b64encode(

tool_call.arguments["new_content"].encode("utf-8")

).decode("utf-8")

update_file(

owner=owner,

repo=repo,

path=tool_call.arguments["path"],

content_b64=content_b64,

message=tool_call.arguments["message"],

branch=state.branch_name or base_branch,

)

outcome = {"updated": tool_call.arguments["path"]}

elif tool_call.name == "create_pull_request":

pr_url = create_pull_request(

owner=owner,

repo=repo,

head=state.branch_name or tool_call.arguments["head"],

base=tool_call.arguments.get("base", base_branch),

title=tool_call.arguments["title"],

body=tool_call.arguments.get("body", ""),

)

outcome = {"pr_url": pr_url}

else:

outcome = {"error": f"Unknown tool {tool_call.name}"}

state.history.append(

{"tool": tool_call.name, "args": tool_call.arguments, "result": outcome}

)

return state.result or "Stopped without explicit finish."

This is the skeleton of a coding agent: with better prompts, tests as tools, and guardrails, it can handle non-trivial feature work, especially in internal services where patterns are consistent.

Production concerns: observability, safety, and governance

Once agents leave your laptop and touch real systems, the boring stuff becomes crucial.

Key concerns:

- Tracing & observability: Capture every tool call, LLM prompt, and decision as a trace for debugging and performance tuning.

- Evaluations: Offline evals on synthetic and real tasks help prevent regressions when you change prompts, tools, or models.

- Governance: Role-based access control, audit trails, and policy checks are increasingly mandatory in regulated environments.

Platforms like Vellum, plus cloud offerings from OpenAI, AWS, and Google, now bundle evaluations, tracing, and governance as first-class features to make production agent deployment feasible for teams of varying maturity.

Where to go next

If you want to go deeper as a developer:

- Start with a single, narrow agent (e.g., “support triage” or “log analysis”) instead of a general assistant.

- Pick a framework aligned with your stack: LangChain/LangGraph or AutoGen for Python-heavy backends, OpenAI Agents SDK if you’re already all-in on OpenAI, or Vellum for teams needing strong observability and governance.

- Treat agents like any other critical service: tests, alerts, dashboards, and rollback plans are non-negotiable.

Used well, agentic AI becomes a force multiplier: not just “smarter autocomplete”, but a programmable colleague that can own whole workflows—with your engineering team firmly in control of the rails it runs on.